Imagine having a conversation with a child and hearing other children deep in discussion,

"Does 1 plus 1 equal 2?"

Silence.

"WHAT?!"

"Dude, no way!! It said no!"

Followed by a chorus "ooooh"

At first glance one would see a group of children asking silly yes or no questions, throwing folded paper, labeled yes/no, into the air and patiently waiting for the response. However, as with all types of interaction and play, something deeper lies beneath.

Some might wonder, what is it about this schema that excites the children? What are they gaining by throwing some paper in the air to answer a yes or no question? Is it the throwing? The children do love creating and tossing paper airplanes. Is it the satisfaction of making each other laugh and connecting with each other? Or is it the anticipation of wondering what side the paper might land on?

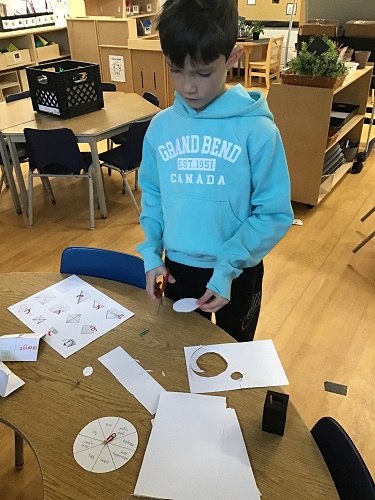

"What should I write in the spaces?" Elora pondered aloud.

"I think I'm only going to make two halves and just write yes in one and no in the other." Finley declared.

"I remember my 8-ball saying ask after lunch, so I'm going to write that." Elora stated.

The children continued to discuss the various words they wanted to write in the spaces on their spinner. Once the spinners were completed, the children took turns asking each other yes/no questions before spinning the paper clip and waiting for it to stop. The positive interactions observed, the relationship building, and community strengthening developing from this activity had us wondering if children enjoy these activities because of the excitement of waiting for the outcome. Are they naturally drawn to probability and chance-based activities?

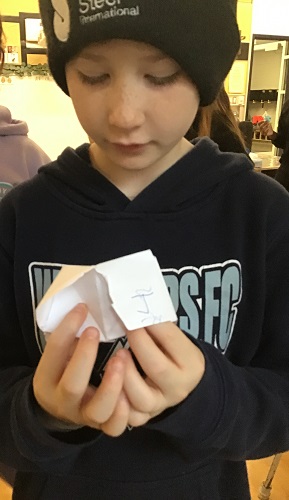

To help us develop a better understanding, the children created their own "cootie catcher" staying with similar yes/no responses that were on the spinners. Although the children showed enjoyment while creating the cootie catchers, the

"I can't pick 6, I remember what it says." Caden insisted.

"Okay, but don't pick number 3 because Emma just did." Spencer reminded them.

It quickly became clear that once the children memorized the numbered flaps, the sense of excitement faded. The unknown was no longer unknown. While they valued the crafting and collaboration, they were less energized than they were with the paper tossing and spinners. This observation strengthened our wonder: Perhaps it is the unpredictability—the true uncertainty of the outcome—that fuels their engagement. The children weren’t just playing; they were exploring chance, probability, and the very human thrill of waiting to see what happens.

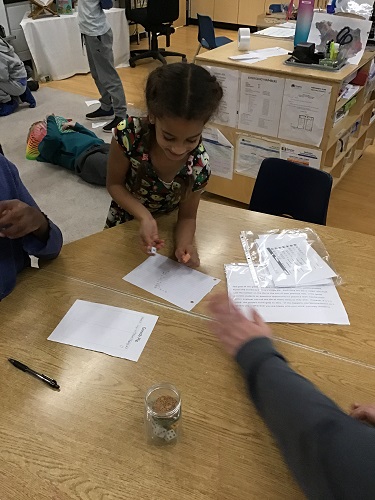

To extend the children’s fascination with chance and prediction, they were invited to create their own version of a Magic 8-ball. Instead of a cube, each child received a small two-sided piece of foam, writing “yes” on one side and “no” on the other. Once their pieces were placed into a glass bottle filled with water and glitter, the wondering began.

A moment later he announced, “Sorry, Mom— the Magic 8-ball told me I don’t need to have a shower!”

Brielle shook her bottle enthusiastically. “Is Stephanie the best teacher ever?!”

When her foam piece floated up, she squealed, “It said yes!”

The children continued to take turns, asking playful yes/no questions about their peers, educators, and the world around them—always making sure their questions were respectful, kind, and fun. Through laughter, prediction, and imaginative thinking, the group explored the ideas of probability, randomness, and social connection in a meaningful, hands-on way.

Understanding that the children had been deeply engaged in activities centered around waiting for the unknown, the educators decided to take a deeper dive into the concept of probability. To extend this interest, a variety of dice-based games were introduced.

At first, the children experimented with Yahtzee, but after some play they concluded that the game took too long and required more patience than they were interested in offering. Recognizing that the children preferred games that were quicker with a more fast-paced response, the educators introduced two new options: Greedy Pig and Blocko.

Greedy Pig is a fast-paced dice game where players try to build up points by rolling a single six-sided die. Each roll adds to their score—unless they roll a 1, which resets the round’s points back to zero. Players can choose to stop rolling at any time, banking what they’ve earned, or take a risk and roll again.

At first, the children enthusiastically rolled over and over, eager to collect as many points as possible. When a 1 appeared and their score dropped to zero, many became frustrated.

“Let’s play again, I have an idea,” Riggins insisted, determined to try a new strategy.

During the second round, Riggins slowed down, paying closer attention to the numbers that appeared.

“Okay, I just rolled a 5 and a 4. I think I’m going to stop there and see what happens next,” he decided thoughtfully.

He passed the turn to the educator, who rolled—and landed on a 1.

“I knew it was going to be a 1!” Riggins shouted with excitement.

With each turn, the children started to recognize patterns and make predictions, showing an emerging understanding of probability. They began weighing the risk of rolling again against the reward of keeping their current points. Rather than rushing, they took their time, thought it through, and used their growing knowledge to guide their decisions.

Through a simple dice game, the children explored chance, strategy, and self-regulation—learning to balance risk with reward and celebrating the thrill of the unknown.

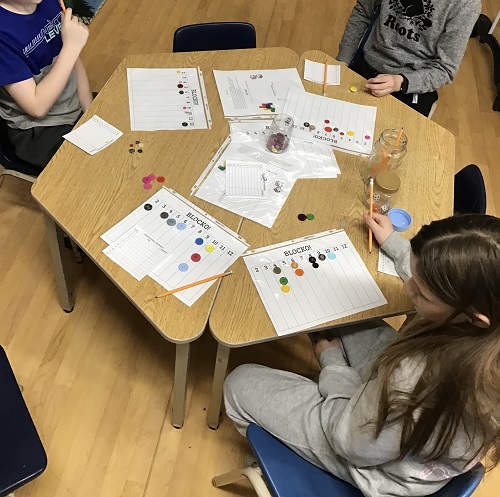

The next game introduced was Blocko. Each child selected 12 blocks (in this case, buttons) and made a prediction about which number on the chart (1–12) would appear most often when rolling two dice. The children placed their 12 buttons on any number or combination of numbers they believed would come up most frequently.

Once all the buttons were placed, the children took turns rolling the dice. Whenever a child rolled a sum that matched a number they had placed a button on, they removed one button. Play continued in this way, with each roll offering a chance to remove another button.

The first child to remove all of their buttons was declared the winner.

During the first round, the children kept track of which numbers were rolled and how often. By the end of the game, they concluded that the number 8 and 12 was rolled the most.

“I am going to put my buttons on mostly 8 and 12 this time.” Emerson insisted while setting up for the second round.

While playing the second round and keeping tallies of each roll, it became clear that the number 8 and 12 were not being rolled as often as the children had initially expected.

“How come we’re not rolling the same numbers that we rolled last game?” Almalinda wondered.

This question naturally led into a conversation about probability and the excitement of the unknown. To begin, the children were asked how many different outcomes there are when rolling a single die. Unsure how to answer, the educators guided them by asking how many sides the die has.

“So, there are 6 sides of the dice, which means that there are 6 different ways the dice could land.” Riggins reasoned.

The educators explained that with one die, the chance of rolling any specific number is 1 out of 6 possible outcomes.

Stephanie then extend ed the thinking: “What do you think the possibility of rolling any number with 2 dice?”

ed the thinking: “What do you think the possibility of rolling any number with 2 dice?”

“Well, if it’s 1 out of 6 chances with 1 dice, then it would be 1 out of 12 chances for 2 dice!” Riggins insisted.

“That’s a really good thought,” Stephanie responded, “however, you have to think about all the different numbers you can roll. So instead of saying 6 plus 6, we would have to think about 6 multiplied by 6.”

“So, the chance of rolling any number with 2 dice is 1 out of 36?! That is sooo many different numbers we could roll.” Riggins confirmed.

Through this discussion, the children began to understand that with 36 possible outcomes, it becomes much harder to predict which sums will appear most often. They also realized that keeping tallies from one game does not necessarily help them predict the next game’s results.

With this new understanding, the children continued to play Blocko—taking turns, sharing ideas, and helping one another decide which numbers might be rolled more or less often, all while enjoying the thrill of the unknown.

These experiences highlighted the children’s natural curiosity about uncertainty, prediction, and the wonder of what might happen. Through paper tossing, spinners, Magic 8-balls, and dice games, the children engaged in rich mathematical thinking without ever being told they were “learning math.” Their conversations, strategies, and questions showed us that probability is not an abstract idea reserved for older learners—it is a concept that children explore intuitively through play.

As educators, we look forward to continuing this inquiry, offering opportunities that nurture curiosity, encourage risk-taking, and honour the joy found in wondering what will happen next?